What the Maduro Affair Reveals About U.S. Policy and Global Precedent

In foreign policy, the most dangerous words are often the calmest ones.

- Law enforcement operation.

- Stability.

- Security.

- Necessary intervention.

These phrases sound administrative. They appear controlled. They have a rational appeal. But history teaches us that behind phrases like these often lie decisions that reshape borders, redefine sovereignty, and quietly recalibrate the rules of global conduct.

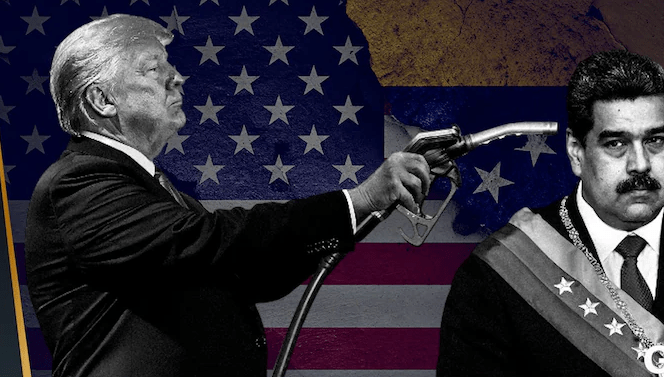

The recent U.S. operation to capture Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro — and the Senate hearing that followed — offers a revealing window into how power is exercised, justified, and explained to the public. More importantly, it forces us to confront an uncomfortable question: What happens when the language of law replaces the language of war?

A Question That Cut Through the Noise

During a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, Senator Rand Paul posed a question that landed with unusual clarity: “If a foreign power entered the United States and removed our president, would we consider that an act of war?”

The question was directed at Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who had repeatedly described the U.S. operation against Maduro as a law enforcement action, not a military one.

Paul’s point was not ideological — it was logical. If such an action would be considered an act of war when done to us, how can it be something else when done by us?

Rubio’s answer reflected the administration’s position: Maduro was not a legitimate head of state but an indicted narcotics trafficker, and therefore his removal did not constitute war. But Paul’s rebuttal lingered: Principles that only work in one direction are not principles at all.

Why Framing Matters More Than Force

The defining feature of this episode is not what happened — but how it was described. By labeling the operation “law enforcement,” the administration avoided constitutional debates over war powers, congressional authorization, and international norms. No declaration. No vote. No formal conflict.

This rhetorical move is not new. Modern foreign policy often relies on linguistic precision to reduce political friction:

- Drone strikes become “counterterrorism actions”

- Sanctions become “economic pressure”

- Regime removal becomes “stability operations”

Yet language does not change consequences. It only changes how they are explained. In this case, U.S. forces removed the leader of a sovereign nation and transferred him to face charges in the United States. Regardless of one’s opinion of Maduro, that action sits in a gray zone that international law was specifically designed to prevent.

Venezuela and the Return of Strategic Realism

Secretary Rubio made no effort to obscure Washington’s broader aims. Venezuela, he argued, had collapsed under corruption, criminal enterprise, and authoritarian rule. Its oil wealth — the largest proven reserves in the world — had been mismanaged and exploited.

Under the new framework, Venezuelan oil revenues would be held under U.S. oversight and released only for approved purposes. The goal, according to the administration, was stabilization, reconstruction, and eventual democratic transition. Critics, however, heard something else.

They heard echoes of earlier eras when economic control followed political intervention. When the line between assistance and administration blurred. When foreign policy was guided less by law than by leverage.

As the BBC noted in its coverage, even U.S. allies expressed unease at how rapidly the operation unfolded and how narrowly the legal justifications were framed.

The Trouble with One-Way Logic

Rand Paul’s objection cuts deeper than partisanship. It raises a fundamental question about international order: If the rules change depending on who holds power, do they still exist at all?

International law survives only when restraint is mutual. When powerful nations reserve exceptions for themselves, they weaken the very structure they depend on to prevent chaos.

This is not a defense of Maduro’s regime. His government presided over economic collapse, repression, and mass emigration. But moral clarity about a leader does not eliminate the need for legal clarity about process. History is littered with examples of interventions justified by certainty — and regretted later.

Why This Matters Beyond Venezuela

This moment matters because it reflects a broader shift. When military actions are reframed as policing, public oversight erodes. When executive authority expands quietly, democratic accountability contracts. When force becomes normalized under softer language, precedent accumulates. And once precedent hardens, it becomes difficult to reverse.

For American citizens, this should prompt reflection rather than reflex. Not about whether Maduro was good or bad — but about what kind of world emerges when nations decide that legality is optional if the cause feels righteous.

Final Thoughts

Power reveals more about a nation than its rhetoric ever can. The strength of a democracy lies not in its ability to act, but in its willingness to restrain itself — especially when restraint is inconvenient. The United States has long claimed moral leadership not because it is flawless, but because it once held itself to standards it expected others to follow.

The question now is whether that tradition endures. Because once the line between law enforcement and war disappears, it rarely returns — and history suggests that the consequences of that loss are rarely felt by those who made the decision, but by those who inherit it.

Leave a comment