For most of the modern era, the United States has lived with a quiet assumption—shared by allies and adversaries alike—that whatever turbulence it experienced domestically, it would eventually right itself. Elections would come and go, administrations would rise and fall, but the deeper architecture of American domestic and global leadership would endure. The country might stumble, but it would not stray too far from its role as the world’s most reliable democratic anchor. That assumption no longer holds.

The most consequential legacy of the Trump presidency is not a specific policy, speech, or scandal. It is the realization—now widely accepted abroad—that American leadership is no longer structurally predictable. What once appeared stable now appears conditional. What once felt permanent now seems provisional. And I posit with great gusto, in the realm of international affairs, perception is reality.

The End of Automatic Trust

For nearly eighty years following World War II, the United States has occupied a unique position in global affairs. Its influence has rested not only on military or economic power, but perhaps most importantly, on credibility. Allies trusted that American commitments would endure beyond electoral cycles. Adversaries understood that U.S. policy, even when forceful, followed discernible rules. Institutions mattered. Continuity mattered.

This trust survived enormous strain. It endured Vietnam, Watergate, periods of economic upheaval, and 9/11, which influenced actions in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars. Even during moments of deep disagreement, American leadership was assumed to be fundamentally anchored in a long-term vision of global order. The Trump years have fractured that assumption.

What has distinguished this period is not simply ideological deviation, but the abandonment of consistency as a governing principle. Dealings with traditional alliances have been treated as transactions. Multilateral institutions have been dismissed as constraints. Diplomatic norms have been openly ridiculed. Longstanding commitments are framed as negotiable, even expendable.

To many Americans, this might appear as refreshing bluntness. In the eyes of the world, it appears as volatility. And volatility is the enemy of trust.

A World Has Moved On

There is a persistent belief within the United States that once political normalcy is restored, the world will simply resume its former posture toward American leadership. This misunderstands how deeply perceptions have shifted.

Reports indicate that across Europe, defense planning increasingly assumes a less reliable United States. In Asia, strategic partnerships are hedged rather than presumed. Even close allies now speak openly of “strategic autonomy”—a phrase that was unnecessary only a short time ago. This is not necessarily a rejection of America. It is an adaptation to uncertainty.

History offers a sobering parallel. After World War I, the United States retreated from global leadership, confident that its moral authority would endure. Instead, the vacuum it left behind contributed to instability that eventually engulfed the world. When the United States re-engaged after World War II, it did so with a recognition that leadership required sustained commitment, not involvement based on short-term transactional gains. Today’s moment is different, but the lesson remains: credibility cannot be switched on and off without consequence.

The Cost of Transactional Leadership

At the heart of the shift lies a philosophy that treats leadership as a series of exchanges rather than a long-term obligation. This transactional view may make sense in business where a bottom line is sought, and strategy can be negotiated quarterly. In geopolitics, it corrodes long-term trust that is crucial for sustained strength both in domestic and foreign relations.

Alliances are not contracts renegotiated at will. They are built on expectations formed over decades. When those expectations are violated—publicly and repeatedly—the damage compounds exponentially.

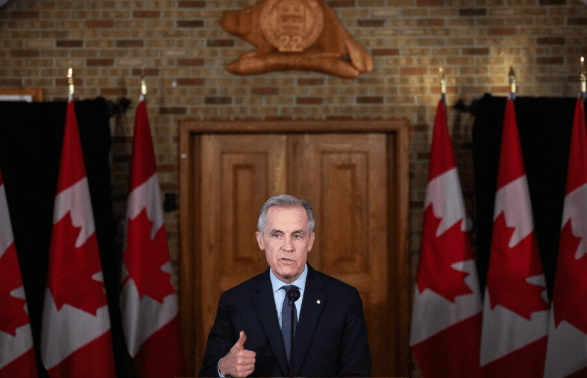

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, former governor of both the Bank of England and the Bank of Canada, has warned that societies governed by short-term thinking ultimately weaken themselves. His critique, aimed largely at financial systems, applies with equal force to foreign and even domestic policy. Stability, he argues, is not the product of constant renegotiation, but of credible continuity.

The Trump presidency embodied the opposite impulse: immediacy over endurance, leverage over legitimacy. The result was not just diplomatic friction, but a recalibration of how the world understands American reliability. The consequences of that recalibration will outlast any single administration.

The Myth of Restoration

Much of today’s political discourse rests on the hope that the United States can simply “return” to its former role. But this hope depends on a myth—that the global order which elevated American leadership still exists in the same form. It does not.

Power is now diffuse. Economic influence is multipolar. Information flows instantaneously and uncontrollably. Domestic politics everywhere are more volatile. The conditions that once allowed the United States to act as an unchallenged anchor of stability have changed.

The question is no longer whether America can reclaim its past role. It is whether it can adapt to a different one.

I argue that leadership for the rest of the twenty-first century is less about dominance than about reliability. Less about command than about coherence. It requires a willingness to operate within constraints rather than above them. Being a reliable hegemon bears lofty responsibility.

Rebuilding and Rebranding a Nation

If American leadership is to regain credibility, it will not happen through rhetoric or symbolism. It will require sustained behavior over time.

First, it requires institutional seriousness. Treaties must endure beyond administrations. Commitments must be honored even when inconvenient. The world must see that American policy is shaped by more than electoral cycles.

Second, it requires humility. The United States must acknowledge that moral authority is not self-declared. It is earned through consistency, accountability, and perhaps the willingness to admit error.

Third, it requires long-term thinking and strategic planning. The central challenges of this century—climate change, technological disruption, democratic resilience, economic inequality—do not yield to short-term solutions. They demand patience, coordination, and restraint; they demand a long-term commitment and consistency of action on the stage of multilateralism.

This is where Carney’s broader argument becomes especially relevant. He has repeatedly emphasized that healthy systems are those designed for durability rather than speed. Applied to geopolitics, this suggests that the most credible leadership today is quiet, steady, and unspectacular. In other words, the opposite of what has recently defined American political culture.

A New Hope

It is tempting to frame this moment as one of decline. But decline is not inevitable. What is ending is not American relevance, but American exceptionalism in its unexamined form.

The United States retains extraordinary strengths. These include institutional depth, cultural influence, innovative capacity, and a tradition—however strained—of self-correction. What remains uncertain is whether it can exercise those strengths with discipline.

The world is no longer waiting nostalgically for America to reclaim its place on a pedestal – that John Winthrop descriptor, “the shining city upon a hill,” the same phrase Ronald Reagan eloquently used in his 1989 farewell address. It is watching to see whether the country can mature into a different kind of leader—one that understands power as stewardship rather than dominance.

There is no going back to the assumptions of the late twentieth century. That era has closed. But there is a path forward.

If the United States can embrace consistency over spectacle, humility over bravado, and cooperation over coercion, it may yet rebuild the trust that once defined it. Not as the world’s unquestioned authority, but as a credible partner in a complex and fragile global order.

Unquestionably, in the long arc of history, that kind of leadership—earned rather than assumed—will prove to be the most enduring form of influence. God bless the USA; God bless all nations of the world!

Leave a comment